3021. Google File System - DraftGFS

Paper of The Google File System.

Google File System is a scalable distributed file system for large distributed & data-intensive applications. This paper is the inspiration for HDFS, the file system that powers Hadoop.

1. Introduction

- Running on inexpensive commodity hardware.

- Component failures are the norm rather than the exception.

- Constant monitoring, error detection, fault tolerance, and automatic recovery must be integral to the system.

- Files are huge.

- Most files are mutated by

appendingnew data rather thanoverwritingexisting data.

2. Design Overview

2.1 Assumptions

- The system is built from many inexpensive commodity components that often fail.

- The system stores a modest number of large files.

- The workloads primarily consist of two kinds of reads:

large streamingreads andsmall randomreads. - The workloads also have many large,

sequential writesthat append data to files. - The system must efficiently implement

well-defined semanticsfor multiple clients that concurrently append to the same file. - High sustained bandwidth is more important than low latency.

2.2 Interface

Usual operations: create, delete, open, close, read, and write files.

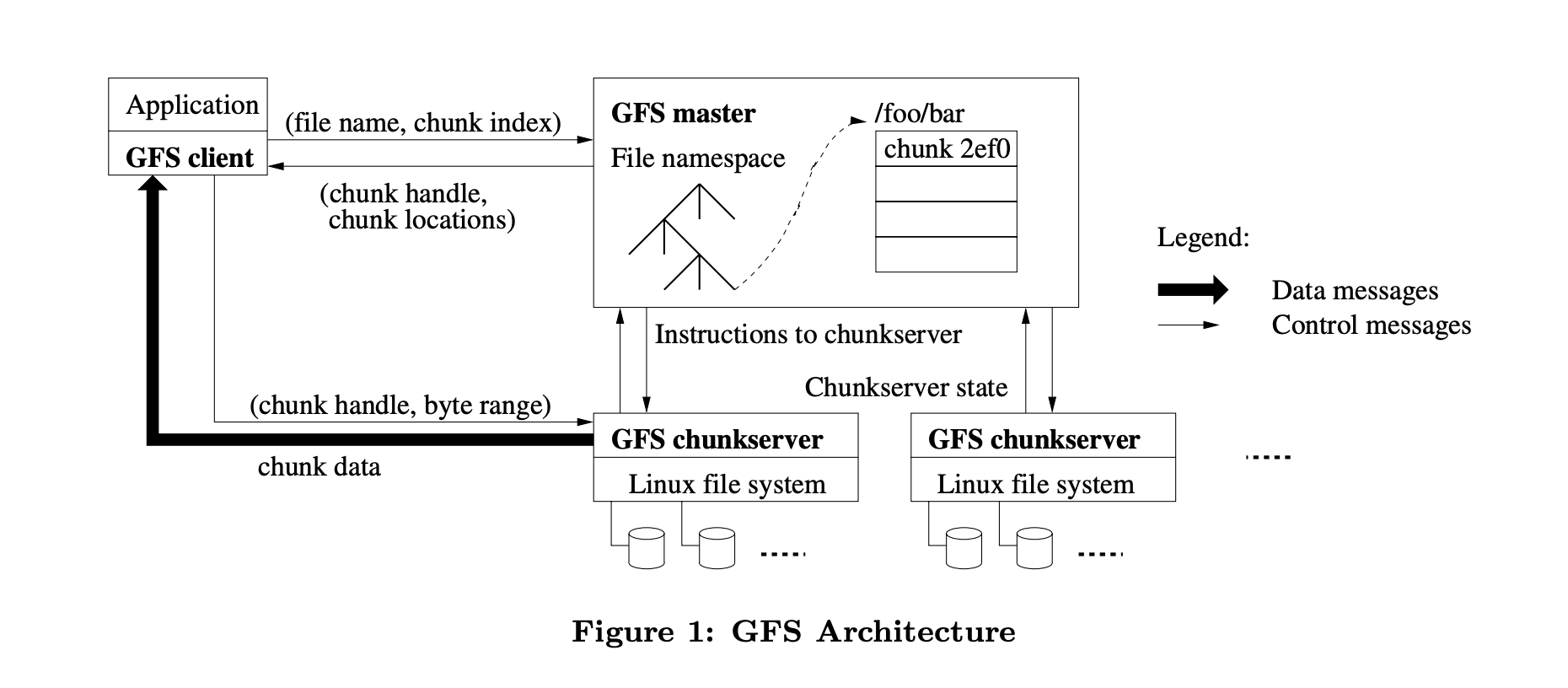

2.3 Architecture

- A GFS cluster consists of a single

masterand multiplechunkserversand is accessed by multiple clients. - The master maintains all file system metadata.

- The master periodically communicates with each chunkserver in

HeartBeatmessages to give it instructions and collect its state. - Files are divided into

fixed-sizechunks. - For reliability, each chunk is replicated three

replicas on multiple chunkservers. - Clients interact with the master for metadata operations, but all data-bearing communication goes directly to the chunkservers.

- Chunkservers need not cache file data because chunks are stored as local files and so Linux’s buffer cache already keeps frequently accessed data in memory.

2.4 Single Master

Clients never read and write file data through the master. Instead, a client asks the master which chunkservers it should contact. It caches this information, using the file name and chunkindex as the key, for a limited time and interacts with the chunkservers directly for many subsequent operations.

2.5 Chunk Size

The default chunk size is 64MB.

2.6 Metadata

The master stores three major types of metadata:

- The file and chunk namespaces.

- The mapping from files to chunks.

- The locations of each chunk’s replicas.

The first two types (namespaces and file-to-chunk mapping) are also kept persistent by logging mutations to an operation log stored on the master’s local disk and replicated on remote machines. Using a log allows us to update the master state simply, reliably, and without risking inconsistencies in the event of a master crash.

2.7 Consistency Model

3. System Interactions

3.1 Leases and Mutation Order

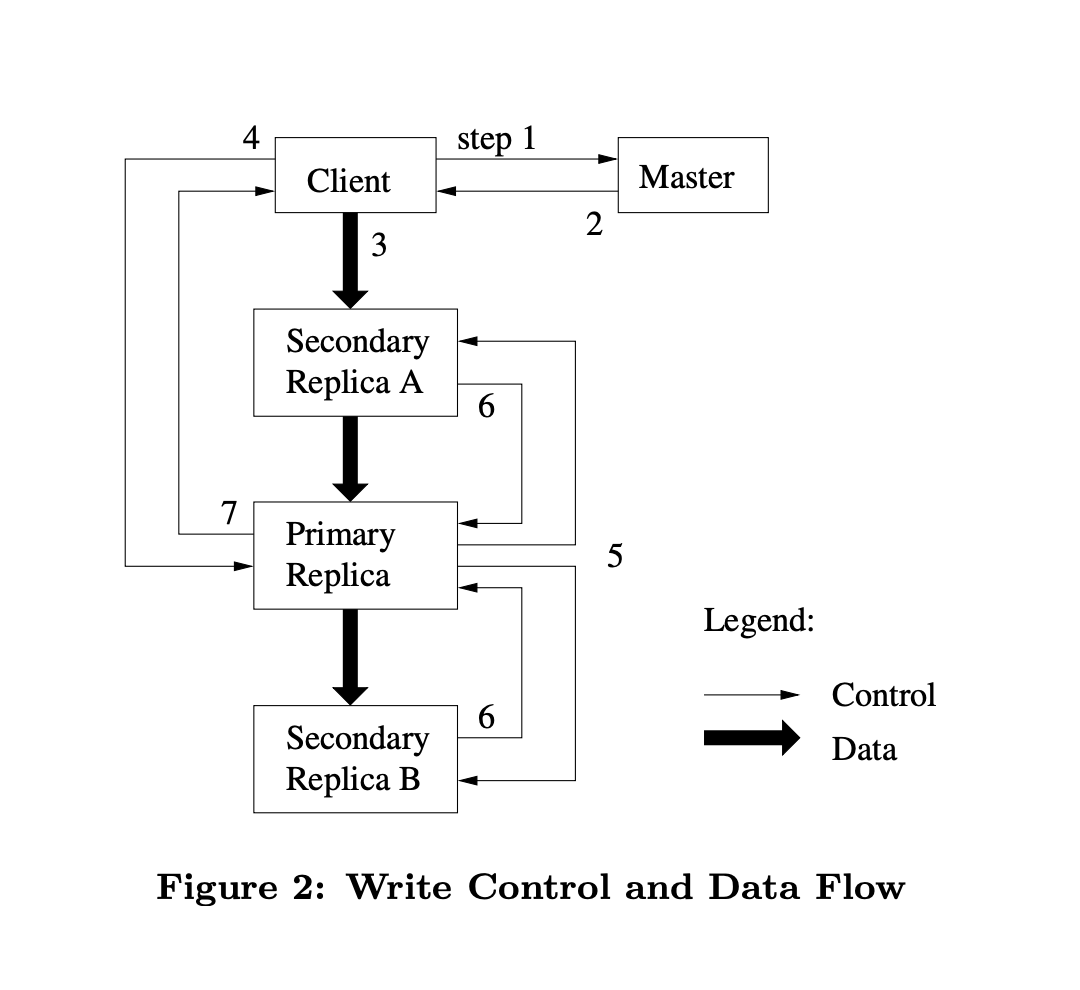

Each mutation is performed at all the chunk’s replicas. We use leases to maintain a consistent mutation order across replicas. The master grants a chunk lease to one of the replicas, which we call the primary. The primary picks a serial order for all mutations to the chunk.

- The client asks the master which chunkserver holds the current lease for the chunkand the locations of the other replicas. If no one has a lease, the master grants one to a replica it chooses.

- The master replies with the identity of the primary and the locations of the other (secondary) replicas. The client caches this data for future mutations. It needs to contact the master again only when the primary becomes unreachable or replies that it no longer holds a lease.

- The client pushes the data to all the replicas. A client can do so in any order. Each chunkserver will store the data in an internal

LRU buffercache until the data is used or aged out. By decoupling the data flow from the control flow, we can improve performance by scheduling the expensive data flow based on the network topology regardless of which chunkserver is the primary. - Once all the replicas have acknowledged receiving the data, the client sends a write request to the primary. The request identifies the data pushed earlier to all of the replicas. The primary assigns consecutive serial numbers to all the mutations it receives, possibly from multiple clients, which provides the necessary serialization. It applies the mutation to its own local state in serial number order.

- The primary forwards the write request to all secondary replicas. Each secondary replica applies mutations in the same serial number order assigned by the primary.

- The secondaries all reply to the primary indicating that they have completed the operation.

- The primary replies to the client. Any errors encountered at any of the replicas are reported to the client.