3226. Nginx - IntroductionNginx

Nginx Architecture.

1. Nginx Overview

1.1 What is Nginx?

Nginx (pronounced “Engine X”) is a high performance web server. It was originally developed to tackle the 10K problem which means serving 10,000 concurrent connections. Nginx can be used as a standalone web server, or serve in front of other web servers as a reverse proxy.

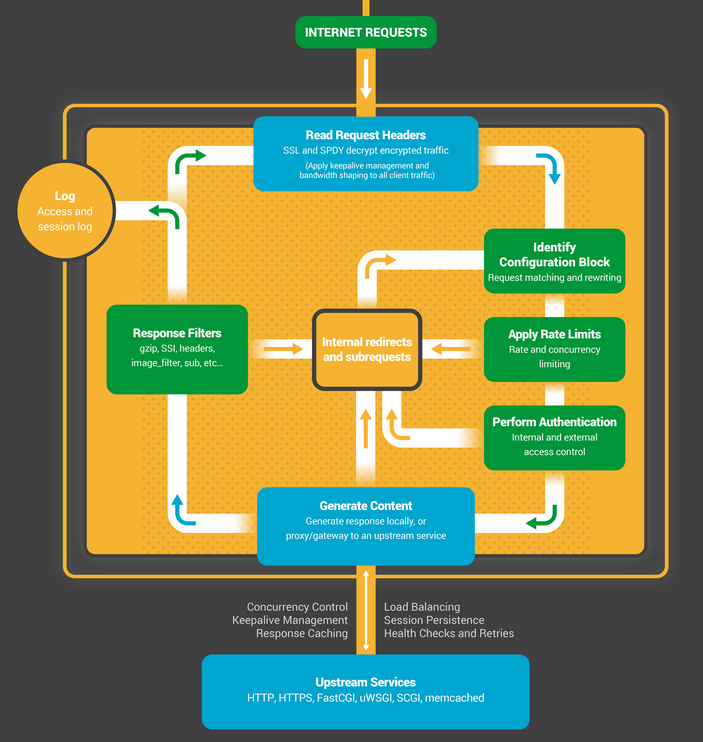

When serving as a reverse proxy, Nginx is acting as a front web server which passes the incoming requests on to web servers on the back, on different ports etc. Nginx can then handle aspects like SSL/HTTPS, GZip, cache headers, load balancing and a lot of other stuff. The web servers on the back then do not need to know how to handle this. And you only have one web server for which you need to learn how to configure SSL/HTTPS, GZip etc.

1.2 Why Nginx is Fast?

Nginx leads the pack in web performance, and it’s all due to the way the software is designed. Whereas many web servers and application servers use a simple threaded or process‑based architecture, Nginx stands out with a sophisticated event‑driven architecture that enables it to scale to hundreds of thousands of concurrent connections on modern hardware.

2. Nginx Architecture

2.1 Why Is Architecture Important?

The fundamental basis of any Unix application is the thread or process. (From the Linux OS perspective, threads and processes are mostly identical; the major difference is the degree to which they share memory.) A thread or process is a self‑contained set of instructions that the operating system can schedule to run on a CPU core. Most complex applications run multiple threads or processes in parallel for two reasons:

- They can use more compute cores at the same time.

- Threads and processes make it very easy to do operations in parallel (for example, to handle multiple connections at the same time).

Processes and threads consume resources. They each use memory and other OS resources, and they need to be swapped on and off the cores (an operation called a context switch). Most modern servers can handle hundreds of small, active threads or processes simultaneously, but performance degrades seriously once memory is exhausted or when high I/O load causes a large volume of context switches.

The common way to design network applications is to assign a thread or process to each connection. This architecture is simple and easy to implement, but it does not scale when the application needs to handle thousands of simultaneous connections.

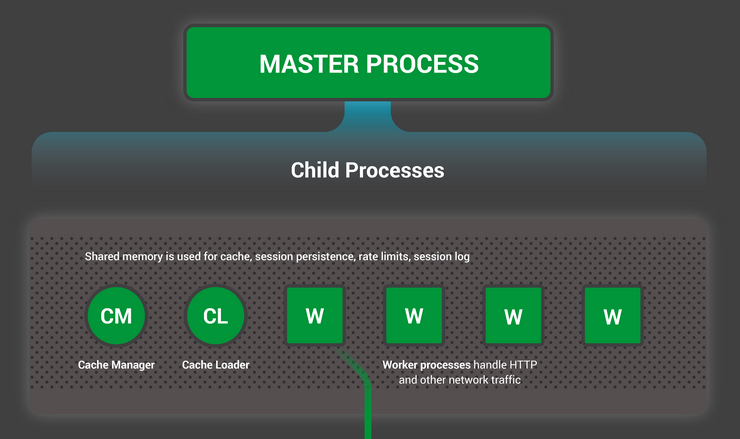

2.2 The Nginx Process Model

How Does Nginx Work? Nginx uses a predictable process model that is tuned to the available hardware resources:

- The

master processperforms the privileged operations such as reading configuration and binding to ports, and then creates a small number of child processes (the next three types). - The

cache loader processruns at startup to load the disk‑based cache into memory, and then exits. It is scheduled conservatively, so its resource demands are low. - The

cache manager processruns periodically and prunes entries from the disk caches to keep them within the configured sizes. - The

worker processesdo all of the work! They handle network connections, read and write content to disk, and communicate with upstream servers.

To better understand this design, you need to understand how Nginx runs. Nginx has a master process (which performs the privileged operations such as reading configuration and binding to ports) and a number of worker and helper processes.

$ service nginx restart

$ ps -ef --forest | grep nginx

root 32475 1 0 13:36 ? 00:00:00 nginx: master process /usr/sbin/nginx

nginx 32476 32475 0 13:36 ? 00:00:00 _ nginx: worker process

nginx 32477 32475 0 13:36 ? 00:00:00 _ nginx: worker process

nginx 32479 32475 0 13:36 ? 00:00:00 _ nginx: worker process

nginx 32480 32475 0 13:36 ? 00:00:00 _ nginx: worker process

nginx 32481 32475 0 13:36 ? 00:00:00 _ nginx: cache manager process

nginx 32482 32475 0 13:36 ? 00:00:00 _ nginx: cache loader process

- On this four‑core server, the Nginx master process creates four worker processes and a couple of cache helper processes which manage the on‑disk content cache.

On mac, try the following command.

ps aux | grep nginx

nobody 1489 0.0 0.0 4294088 1176 ?? S 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: worker process

nobody 1488 0.0 0.0 4285896 1192 ?? S 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: worker process

nobody 1487 0.0 0.0 4296136 1188 ?? S 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: worker process

nobody 1486 0.0 0.0 4296136 1212 ?? S 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: worker process

nobody 1485 0.0 0.0 4301256 1184 ?? S 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: worker process

nobody 1484 0.0 0.0 4294088 1184 ?? S 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: worker process

nobody 1483 0.0 0.0 4296136 1204 ?? S 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: worker process

nobody 1482 0.0 0.0 4294088 1180 ?? S 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: worker process

root 1481 0.0 0.0 4275984 556 ?? Ss 10:06PM 0:00.00 nginx: master process nginx

The Nginx configuration recommended in most cases – running one worker process per CPU core – makes the most efficient use of hardware resources. You configure it by setting the auto parameter on the worker_processes directive:

worker_processes auto;

When an Nginx server is active, only the worker processes are busy. Each worker process handles multiple connections in a nonblocking fashion, reducing the number of context switches.

Each worker process is single‑threaded and runs independently, grabbing new connections and processing them. The processes can communicate using shared memory for shared cache data, session persistence data, and other shared resources.

2.3 Nginx Worker Process

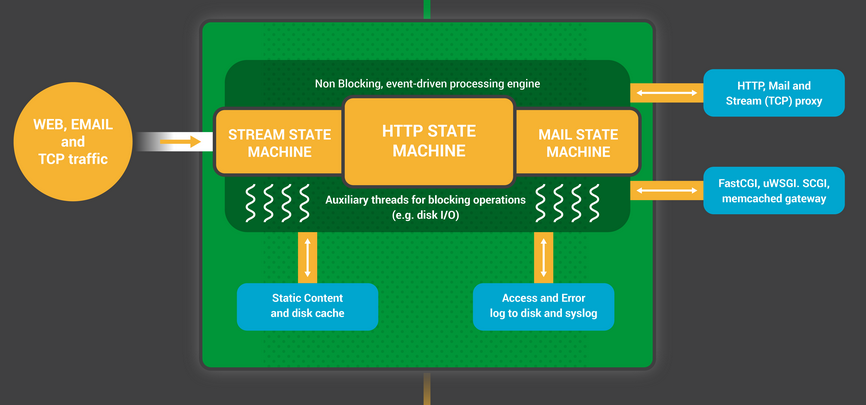

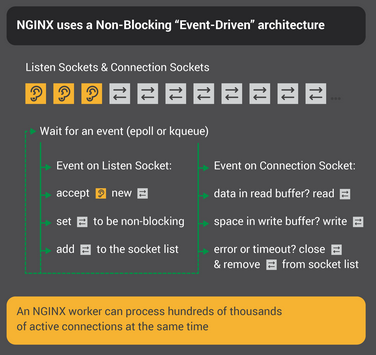

Each Nginx worker process is initialized with the Nginx configuration and is provided with a set of listen sockets by the master process.

The Nginx worker processes begin by waiting for events on the listen sockets (

The Nginx worker processes begin by waiting for events on the listen sockets (accept_mutex and kernel socket sharding). Events are initiated by new incoming connections. These connections are assigned to a state machine – the HTTP state machine is the most commonly used, but Nginx also implements state machines for stream (raw TCP) traffic and for a number of mail protocols (SMTP, IMAP, and POP3).

The state machine is essentially the set of instructions that tell Nginx how to process a request. Most web servers that perform the same functions as Nginx use a similar state machine – the difference lies in the implementation.

The state machine is essentially the set of instructions that tell Nginx how to process a request. Most web servers that perform the same functions as Nginx use a similar state machine – the difference lies in the implementation.

2.4 Scheduling the State Machine

Think of the state machine like the rules for chess. Each HTTP transaction is a chess game. On one side of the chessboard is the web server – a grandmaster who can make decisions very quickly. On the other side is the remote client – the web browser that is accessing the site or application over a relatively slow network.

However, the rules of the game can be very complicated. For example, the web server might need to communicate with other parties (proxying to an upstream application) or talk to an authentication server. Third‑party modules in the web server can even extend the rules of the game.

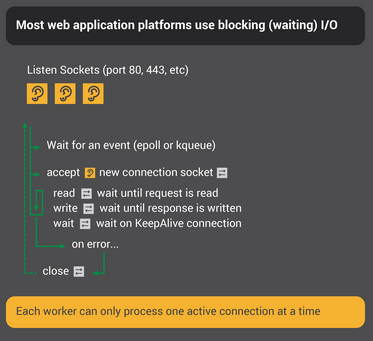

1) A Blocking State Machine

Recall our description of a process or thread as a self‑contained set of instructions that the operating system can schedule to run on a CPU core. Most web servers and web applications use a process‑per‑connection or thread‑per‑connection model to play the chess game. Each process or thread contains the instructions to play one game through to the end. During the time the process is run by the server, it spends most of its time ‘blocked’ – waiting for the client to complete its next move.

- The web server process listens for new connections (new games initiated by clients) on the listen sockets.

- When it gets a new game, it plays that game, blocking after each move to wait for the client’s response.

- Once the game completes, the web server process might wait to see if the client wants to start a new game (this corresponds to a keepalive connection). If the connection is closed (the client goes away or a timeout occurs), the web server process returns to listening for new games.

The important point to remember is that every active HTTP connection (every chess game) requires a dedicated process or thread (a grandmaster). This architecture is simple and easy to extend with third‑party modules (‘new rules’). However, there’s a huge imbalance: the rather lightweight HTTP connection, represented by a file descriptor and a small amount of memory, maps to a separate thread or process, a very heavyweight operating system object. It’s a programming convenience, but it’s massively wasteful.

2) Nginx is a True Grandmaster

Each worker (remember – there’s usually one worker for each CPU core) is a grandmaster that can play hundreds (in fact, hundreds of thousands) of games simultaneously.

- The worker waits for events on the listen and connection sockets.

- Events occur on the sockets and the worker handles them:

- An event on the listen socket means that a client has started a new chess game. The worker creates a new connection socket.

- An event on a connection socket means that the client has made a new move. The worker responds promptly.

A worker never blocks on network traffic, waiting for its “opponent” (the client) to respond. When it has made its move, the worker immediately proceeds to other games where moves are waiting to be processed, or welcomes new players in the door.

3) Why Is This Faster than a Blocking, Multiprocess Architecture?

Nginx scales very well to support hundreds of thousands of connections per worker process. Each new connection creates another file descriptor and consumes a small amount of additional memory in the worker process. There is very little additional overhead per connection. Nginx processes can remain pinned to CPUs. Context switches are relatively infrequent and occur when there is no work to be done.

In the blocking, connection‑per‑process approach, each connection requires a large amount of additional resources and overhead, and context switches (swapping from one process to another) are very frequent.

For a more detailed explanation, check out this article about NGINX architecture, by Andrew Alexeev, VP of Corporate Development and Co‑Founder at NGINX, Inc.

With appropriate system tuning, Nginx can scale to handle hundreds of thousands of concurrent HTTP connections per worker process, and can absorb traffic spikes (an influx of new games) without missing a beat.

3. Updating and Upgrading

3.1 Updating Configuration

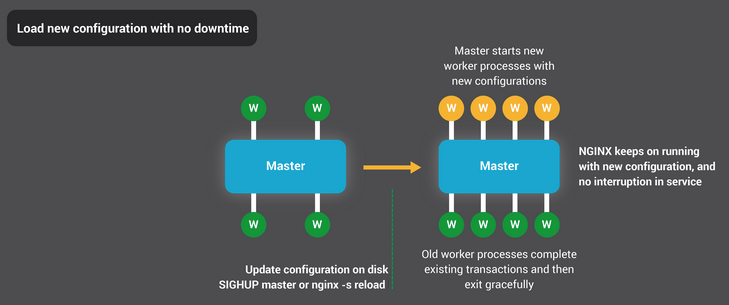

Nginx’s process architecture, with a small number of worker processes, makes for very efficient updating of the configuration and even the Nginx binary itself.

Updating Nginx configuration is a very simple, lightweight, and reliable operation. It typically just means running the

Updating Nginx configuration is a very simple, lightweight, and reliable operation. It typically just means running the nginx -s reload command, which checks the configuration on disk and sends the master process a SIGHUP signal.

When the master process receives a SIGHUP, it does two things:

- Reloads the configuration and forks a new set of worker processes. These new worker processes immediately begin accepting connections and processing traffic (using the new configuration settings).

- Signals the old worker processes to gracefully exit. The worker processes stop accepting new connections. As soon as each current HTTP request completes, the worker process cleanly shuts down the connection (that is, there are no lingering keepalives). Once all connections are closed, the worker processes exit.

This reload process can cause a small spike in CPU and memory usage, but it’s generally imperceptible compared to the resource load from active connections. You can reload the configuration multiple times per second (and many Nginx users do exactly that). Very rarely, issues arise when there are many generations of Nginx worker processes waiting for connections to close, but even those are quickly resolved.

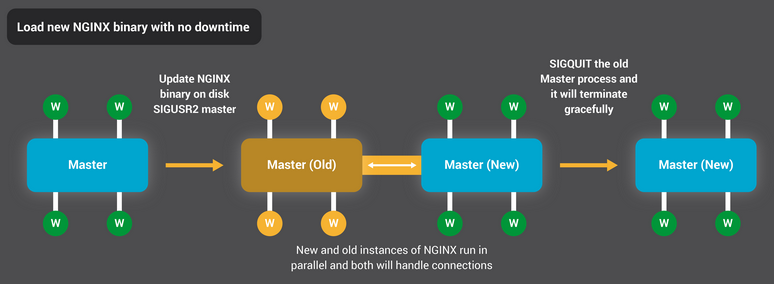

3.2 Upgrading Binary

Nginx’s binary upgrade process achieves the Holy Grail of high availability – you can upgrade the software on the fly, without any dropped connections, downtime, or interruption in service.

The binary upgrade process is similar in approach to the graceful reload of configuration. A new Nginx master process runs in parallel with the original master process, and they share the listening sockets. Both processes are active, and their respective worker processes handle traffic. You can then signal the old master and its workers to gracefully exit.